Current Exhibits

Land of Joy and Sorrow

Japanese Pioneers in the Yakima Valley

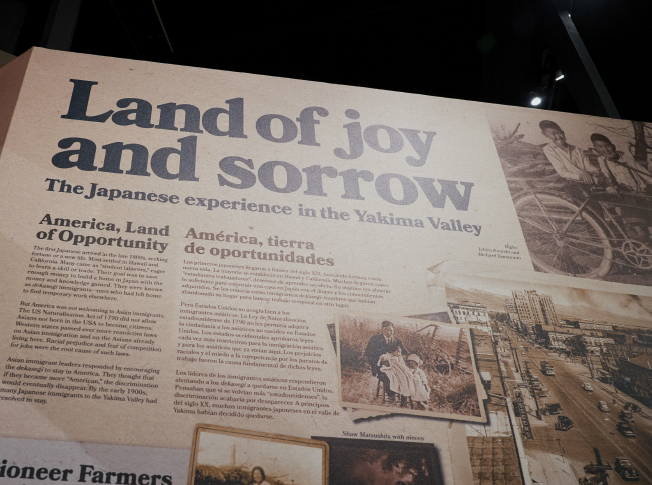

At the turn of the twentieth century, many Japanese families immigrated to the United States.

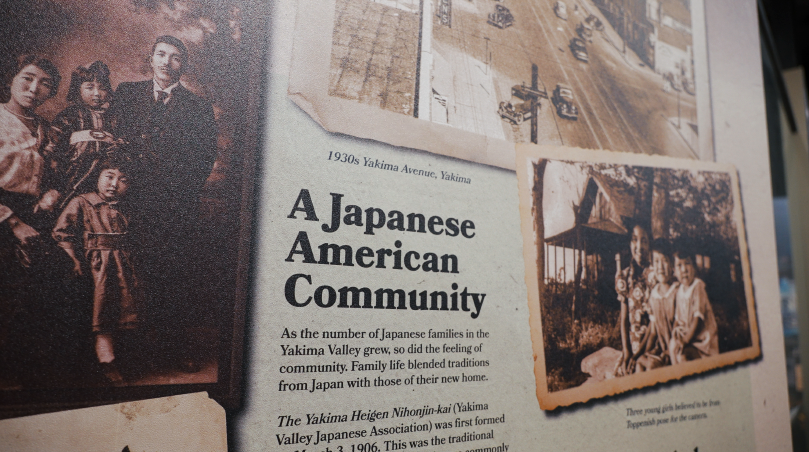

Some were farmers who chose the Wapato-Toppenish area of the lower Yakima Valley as the place to make a new life for themselves because of the potential for agriculture there. Leasing land on the Yakama Indian Reservation, these farmers worked hard to turn the acres of rock and sagebrush into fertile fields, eventually cultivating thousands of acres of lush, diverse crops. They built close-knit farming communities with schools, shops, churches, and civic organizations such as the Japanese Association.

During the 1920s, anti-Japanese feelings began to develop in the United States, leading to the passing of anti-alien land acts in Washington State in 1921 and 1923—suspending the right of Japanese residents to own land. Many Japanese families gave up farming and left the Valley during this time. Those who stayed were required to reduce the amount of acreage they farmed, and sometimes, they were forced to rent their land to other farmers.

Nonetheless, the community persevered and continued to function as normally as possible. But after the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, everything changed. The United States declared war on Japan and all Japanese residents—no matter how long they had lived in this country or what good and productive citizens they had been—came under suspicion.

On February 19, 1942, Executive Order 9066 was signed, commanding all Japanese and Japanese-Americans to be relocated away from the West Coast and resettled in inland camps. The community leaders were the first to be rounded up and removed. But by September 1942, all those of Japanese ancestry living within 150 miles of the Pacific Ocean had been moved to the relocation camps. This totaled 110,000 persons, two-thirds of whom were United States citizens.

Members of the Yakima Valley Japanese community, allowed to take only what they could carry, were shipped to an assembly center in north Portland, Oregon—which also acted as the collection point for Japanese living in Oregon and central California.

All relocated persons were housed in a barn-like structure, which had previously been the Pacific International Livestock Exposition Building. With small apartments partitioned off by plywood and everyone using common toilets, there was little privacy,

After about a month, the Japanese from the Yakima Valley were sent on to their final destination, the relocation camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming. It had 468 barracks and 49 mess halls for approximately I0,000 people from around the country. During its existence, it was the third-largest city in Wyoming. Barbed wire and guard towers around the perimeter were a constant reminder that the inhabitants could not leave.

When the war ended in 1945, the Japanese at Heart Mountain were able to go home. However, many found that their family farms and businesses had been sold in their absence. As a result, fewer than ten percent of those who came from the Yakima Valley returned here, and those who did were often discriminated against. While not being allowed the same privileges as before the war, they also regularly came across signs saying "Whites Only" and "No Japs"—posted in many store windows.